As teachers, we strive to make reaching every learning goal as fun as possible. Teaching in-text citations can be challenging because students find citations confusing. To add to our struggles, grammar is one of the least exciting concepts to teach. Fortunately, there are learning strategies that can motivate students to practice this skill. This blog post will provide you with ideas to help with teaching in-text citations.

What are In-Text Citations?

In-text citations work together with a works cited page to indicate the origins of an idea. The idea could be word-for-word or paraphrased. As the name suggests, in-text citations exist within the text of an essay or paragraph. The role of the in-text citation is to direct the reader to a specific citation within the works cited page, which will then direct them to the original source of the quotation or idea.

Why is Practicing In-Text Citations Important?

Since in-text citations help to indicate the origins of an idea, this skill is a key component for coaching students to avoid plagiarism. It is therefore important for students to understand the purpose of in-text citations in their academic writing.

The ability to read in-text citations is an important aspect of media literacy, too. Whenever students interpret information in electronic or print format, they need to be able to determine the source of that information to assess the credibility of the source.

What Requires an In-Text Citation?

Students must understand that they need to cite any idea, or phrasing of an idea, that is not their own. This may seem obvious, but it’s always a good idea to clarify this to students anyway.

Even if your students have learned about in-text citations before, it is helpful to start from square one. This will prevent any confusion when it comes time to practice citation skills. It also lays the proper foundation for avoiding plagiarism in your students’ writing.

When introducing students to in-text citations, I provide my students with the following two maxims to help them with the placement of in-text citations:

- “Start with the source, end with the spot; what’s in between, the source’s thoughts.”

In other words: start your paragraph with a sentence that mentions the book/article and the author. Everything you write after that and before the page number in parentheses at the end of the paragraph is based on that source. Anything after the page number is your own idea. - “Parentheses mark the spot; before is the source, after is not.”

In other words: If you put the author and page number in parentheses at the end of a sentence, that sentence is based on the source. Anything before that sentence or after the parentheses is your own idea.

Teaching In-Text Citations in Middle School

Many curriculums indicate that students should begin indicating the source of their research as early as Grade 7. The Ontario Curriculum requires students to start examining text features, including references and work cited, in 7th grade. Similarly, the Common Core requires students to “use technology, including the Internet, to produce and publish writing and link to and cite sources.”

You can begin teaching in-text citations by first differentiating between direct wording and ideas. Students should understand that both require a citation. They should also understand the different ways to reference these in their writing. A great way to scaffold this lesson is to begin with a lesson on paraphrasing. When students understand the difference between paraphrasing and a direct quotation, they can begin to understand the different ways to reference information in their research writing.

Scaffolding In-Text Citations in Middle School

A great way to begin teaching in-text citations for both direct quotations and paraphrased ideas is to model the process. You can pick a topic to write about. Then, call on a student to share a thought or idea about the topic. Write the quotation down on your board or projector.

You can write two different paragraphs using the student’s ideas. In one paragraph, include the student’s direct words in quotations. In the other, paraphrase the student’s idea. Ask students what happens if you leave out a reference to the student. Then, ask them how they would attribute the information to the student. You might have some students that already know the answer to these questions; if you don’t, you can show them.

This inquiry-based method is a great way to begin teaching in-text citations because it will prompt students to consider why they need to cite. You can continue this method by asking more questions, including “where should we place the citation?” or “how many sentences within the paragraph are attributed to the author when I place the citation here?”

These types of questions may even get students thinking about how to attribute an entire paragraph or summary to a source. If so, then your students are ready to begin learning about parenthetical and integrated in-text citations. You can teach the difference between these two types of in-text citations by showing students examples of writing using high-interest topics.

Teaching In-Text Citations in High School

By the time students are in Grade 9, they should know how to include in-text citations in their research writing. If they haven’t differentiated between parenthetical and integrated in-text citations, they should also practice this differentiation.

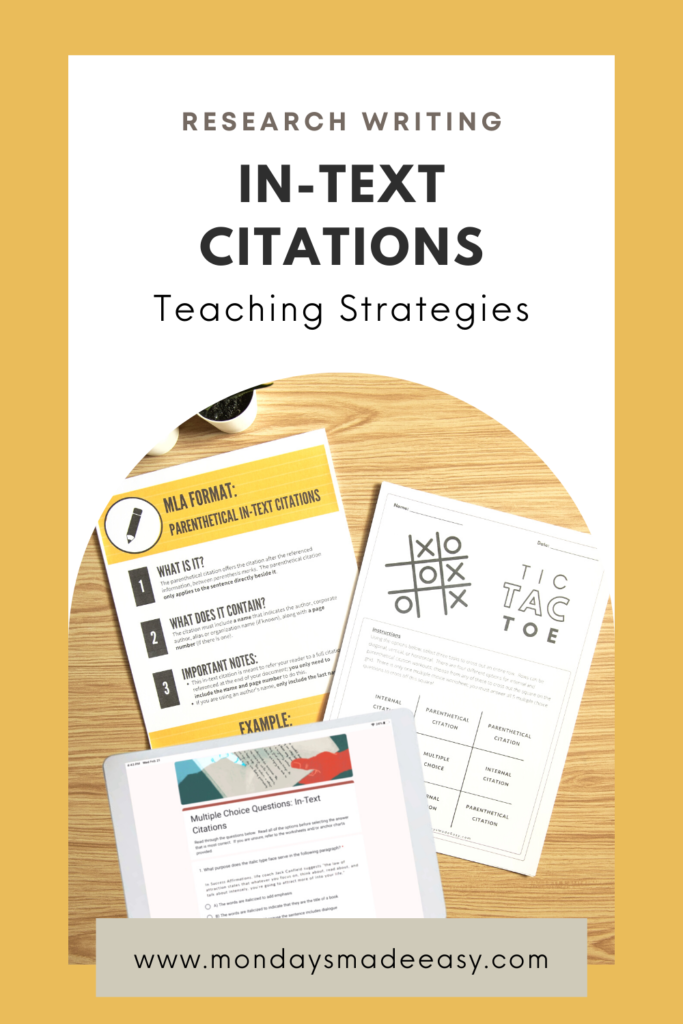

I like to include anchor chart posters in my classroom to demonstrate the difference between these two types of in-text citations. Your anchor charts should include examples of in-text citations to model how to use them in writing. Students can refer to these posters while they practice research writing.

In-Text Citations Activities for High School Students

In addition to practicing writing with in-text citations, another great activity for high school students is to answer multiple-choice sets. Multiple-choice questions are a great test prep for students who will write standardized tests. Although these standardized exams do not assess in-text citations, students can still prepare for their exams by recognizing sentence stems and practicing narrowing down their answers.

Another great thing about multiple-choice questions is that they are a great way to draw attention to subtle differences in grammar and punctuation. Here is an example of a multiple-choice question you could use:

- Which of the following options correctly places the in-text citation?

a) The island of Sørburøy only has 35 inhabitants. (National Geographic, 35)

b) The island of Sørburøy only has 35 inhabitants (National Geographic, 35).

c) The island of Sørburøy only has 35 inhabitants (National Geographic 35).

d) The island of Sørburøy only has 35 inhabitants. (National Geographic 35)

As you can see, the options above are all quite similar. The correct answer is b, but the variations demonstrate common mistakes that students make when placing in-text citations in their writing.

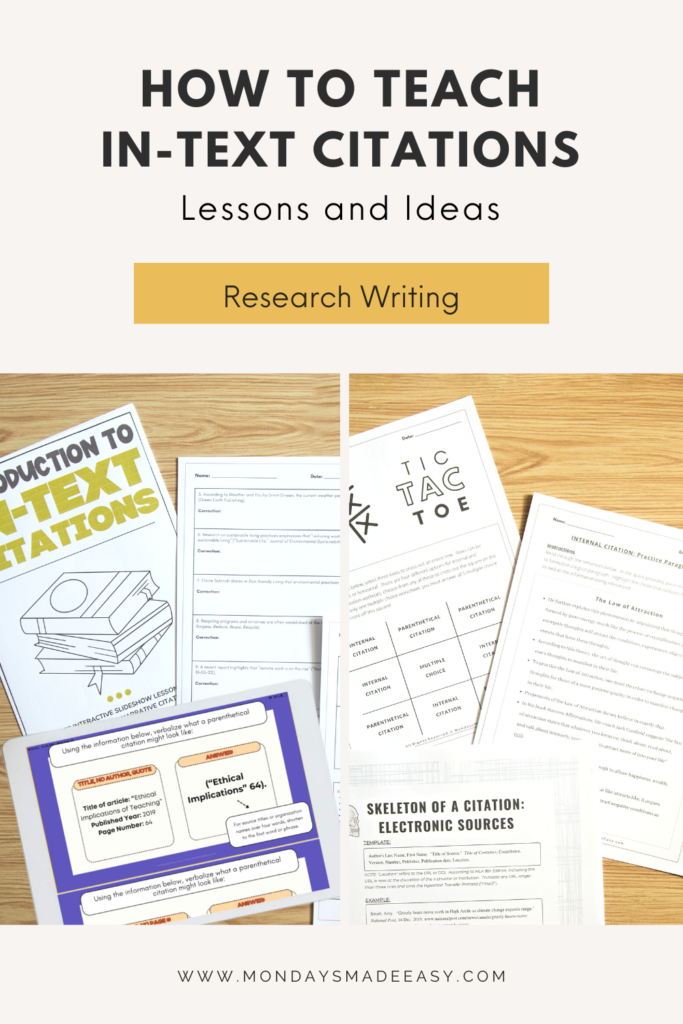

These in-text citations worksheets include a set of 5 multiple-choice questions. These questions quiz students on where to place an in-text citation in a paragraph, what information should be included in an in-text citation, and other important concepts. This resource also includes a Tic-Tac-Toe worksheet to gamify in-text citations practice. Through student choice, students will complete a number of worksheets that have them practice integrating internal and parenthetical in-text citations.

Learning Strategies for Teaching In-Text Citations

Teaching in-text citations may not be the most exciting subject in English, but it can still be engaging. The different learning strategies mentioned in this blog post are featured in this in-text citation unit. This unit includes a slideshow lesson, tic-tac-toe game, various practice activities, multiple-choice questions, anchor chart posters, and more.

To preview this unit, click here.