An Important Disclaimer

Behavioral intervention is a subject that requires a delicate approach. I’d like to begin by acknowledging one of many considerations. 2020 has been a progressive year in addressing systemic racism and racial injustice; for some of us, this may have meant a new opportunity to reflect on our ideologies and worldviews, along with how these shape our interactions within schools. For me, I have come to recognize my role in upholding the dominant culture in Canada. I also recognize that I am hosted on traditional territories of many First Nations peoples, including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples. I acknowledge that First Nations people differ in their cultural approaches towards discipline and behavioral mediation. I recognize that there is more work to be done to understand these differences, as well as differences across many other cultures.

Our global classrooms should uphold the virtues of diversity and inclusion; this is especially true when members of diverse cultures and communities are represented in our student body, but remains true regardless of the identities of our students. This is because diversity and inclusion are societal virtues, and in order to instill these in our students, we must foster diverse attitudes and worldviews in our classrooms. Understanding the cultural implications of behavioral intervention can help us continue to support our students and evolve as educators.

Behavioral intervention will differ greatly depending on the unique needs of our students. While the strategies and advice offered in this blog post are meant to appeal to all classrooms, it is worth noting that there are specific considerations that must be made for behavioral intervention within neurodivergent populations. Research indicates that individuals with learning disabilities are less likely to predict consequences for negative behavior; they are also more likely to choose socially unacceptable behaviors and experience isolation and rejection from their peers. An approach to behavioral intervention that reflects these attributes will best support students with special needs.

Attitudes Towards Behaviour

“Kids with behavioral challenges are not attention-seeking, manipulative, limit-testing, coercive, or unmotivated. But they do lack the skills to behave appropriately. Adults can help by recognizing what causes their difficult behaviors and teaching kids the skills they need.”

– Ross Greene

The dialogue surrounding behavioral students can often address manipulation, motivation, limit-testing, and lack of discipline. But addressing behavioral intervention requires us to start by addressing the attitudes we might have towards these students. We can never truly know the cause or motivation of student behavior, and it can never serve our students to see their identity and their behavior as indistinguishable.

An objective view of behavior will promote a constructive approach toward intervention. When describing behavior, be sure to rely on your observations rather than your conclusions. Attaching meaning to behavior may simply be an attempt to gain a deeper understanding, but it risks misrepresenting a student or misinterpreting their intentions. This can actually move us in the opposite direction of a solution. For example, if a student is consistently late for their first-period class, it is more useful for your colleagues to know that this student arrives 30 minutes after the bell three times a week than it is to hear that this student is unmotivated or doesn’t respect your classroom rules. Objective observation will provide your team with useful data and will also foster a constructive relationship with the student as they continue to be recognized as separate from their behavior.

Similarly, viewing behavior as a cultivated skill rather than an inherent trait will also support our approach to intervention. Educators are quite accustomed to fostering an environment of growth when it comes to multiple intelligences – when our students struggle with spelling, we don’t question their linguistic intelligence. When they make errors in mathematics, we don’t expect them to inherently understand their mistakes. When students don’t excel at a sport or master an instrument, as educators, we interpret these as opportunities for growth. If we can approach linguistic, mathematic, musical, and other subject-based intelligence with encouragement, why can’t we do the same for emotional intelligence?

Emotional Intelligence

Perhaps we think that emotional intelligence is an inherent trait because some students seem more self-aware of their actions than others. Or perhaps we are more easily upset by negative behaviors because the very nature of it elicits an emotional response. Regardless, when we discuss behavior, we must begin to recognize that we are discussing another form of intelligence.

Emotional intelligence refers to the perception, understanding, and management of emotions. A single event within your classroom can elicit a unique interpretation and response from each student. For example, let’s imagine a student has persistent questions about a new topic in your class. They might interpret that you are annoyed, or that they lack the capacity to understand the topic. These emotions might cause them to feel frustrated or embarrassed, and in response to these emotions, they might disengage from the lesson or attempt to draw attention to another student in the class. In contrast, a different student in the same situation might interpret you as impressed with their commitment to understanding the new topic. This might leave them feeling acknowledged and determined, and might motivate them to explore this topic for an upcoming independent study unit.

There are so many variables that contribute to emotional intelligence, and each one manifests as a different outcome for each individual in any given situation. Several factors influence the development of the brain, including parental rejection, traumatic memory, and biological characteristics. Because of the unique lived experience of each of our students, we can never fully understand the way they process the emotions attached to situations within our classroom. However, as a teacher, we do have the opportunity to foster a student’s emotional intelligence. This is because a student’s experience in school is another shaping factor for emotional intelligence – and a significant one at that!

The Goals of Misbehaviour

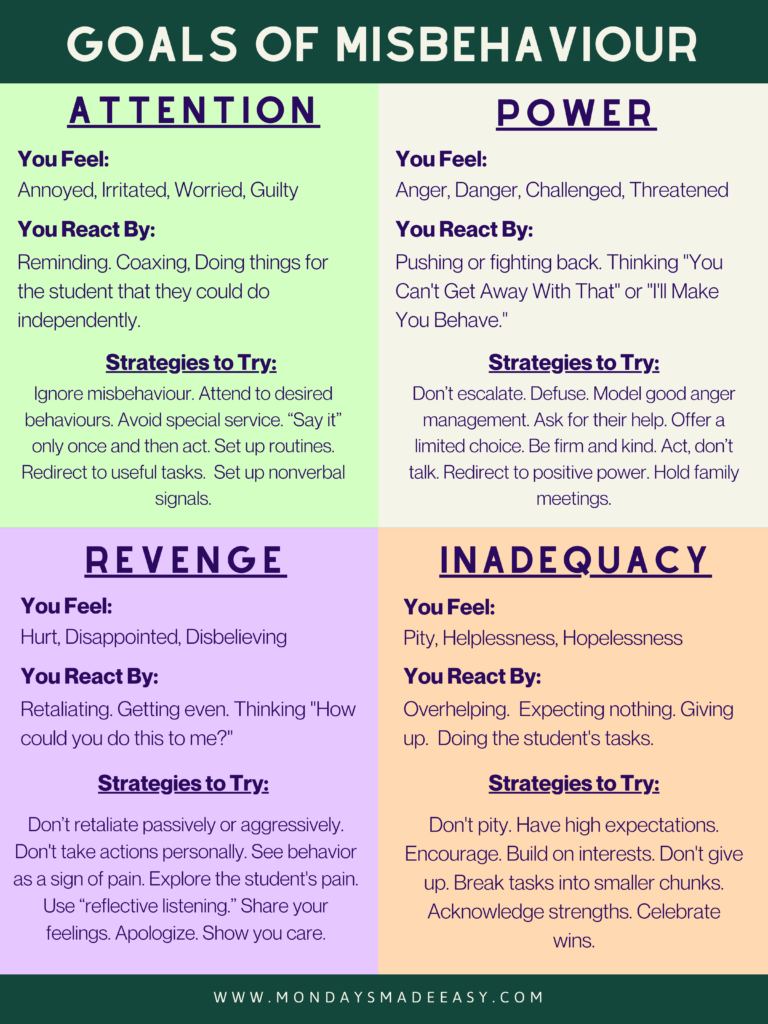

You might be familiar with Rudolf Dreikur’s Four Goals of Misbehaviour. What I love about this theory is that it offers actionable responses to common behaviors within the classroom, and it uses our own emotional response as an indicator of how this behavior can be characterized. I mentioned earlier that I personally find hypothesizing the motivation behind misbehavior to be unproductive; nevertheless, this theory addresses presumed motivations. I’ve summarized the theory below and have included these presumed motivations as it helps to reinforce the information in a cohesive way. Approach these motivations with a grain of salt as we can never simplify the complex behavior of our students; instead, consider the strategies offered in relation to the feelings and reactions you may encounter when dealing with misbehavior.

Universal Prevention

The best intervention for disruptive behaviors is prevention. Universal prevention measures establish a positive classroom environment to make your job easier, but also to support the academic and social potential of each student in your class. Here are some strategies that can be implemented in your classroom, as well as a school-wide approach:

- Positive Relationships: Positive relationships are argued to be the “most powerful weapon available to secondary teachers who want to foster a favorable learning climate,” but building these relationships is easier said than done. Positive relationships require effort and time; to keep us accountable, there are some strategies we can use and data we can collect. One strategy involves considering our students’ “emotional bank accounts.” For each negative or constructive interaction, we should be sure to deposit three to four positive interactions. We can use a spreadsheet to document this information and record rough estimates at the end of each class. Another strategy involves monitoring the learning opportunities we provide to our students. We can place a checkmark next to each student each time we call on them to help us determine whether or not we are being equitable. A positive learning environment does not overlook students who may be reluctant to participate or may have a tendency to underperform academically. When you call on students, show them you believe in them by offering them time to work through their answers; raise the bar high for all of the students in your class and keep it there.

- Learning Environment: Additional preventative measures include differentiated instruction, organization, and the engagement of students’ learning styles. An organized classroom and established routine fosters a positive learning environment and clarifies expectations. A predictable schedule implies the rules; students can deduce what their responsibilities are and how they are expected to behave. Additionally, when students’ individual learning styles and capabilities are accounted for, there is less motivation to require attention, struggle for power, seek revenge, or express inadequacy.

- Peer Leadership: Peer leadership is another great universal prevention strategy, especially for secondary students. Through the role of influencing, supporting, and modeling, students can contribute to the positive environment of their classroom and their school. A great way to foster peer leadership is to develop a school-wide program. This process requires a facilitator or advisor who is able to invite students who reflect the student population to participate. Advisors must recognize the power of youth for promoting change, and collaborate with them to foster a positive school culture. These efforts will not go unnoticed; according to Alberta Health Services, “a peer leadership program can help students, especially those who might not otherwise be in a leadership role, gain important skills to become role models within their schools and communities. In some cases, peer leadership can change the status quo around bullying and other school conflicts.”

- Parental Engagement: Welcome parents into the classroom on day one. How you do this is up to you – this can be as minimal as touching base with parents to let them know what is happening in class. For more involvement, you can invite parents to collaborate with learning and join the physical classroom space. Parents are important members of our school community and significant representatives of school culture. They can serve as role models and mentors for your students and can offer additional support for all children. I love to have parents join the classroom as guest speakers, or even to participate in crucial conversations with my students.

- Classroom Contract: Finally, do not underestimate the need for a classroom contract. While your expectations may seem straightforward, it is important to consider that every teacher’s understanding of a positive classroom environment may look different. Your understanding of respect may be different than your colleagues; more importantly, respect might look different to your students. Classroom contracts should be clearly worded and framed positively using what is called “love and logic language;” this involves outlining the positive behaviors and consequences you’d like to see. For example, “when we raise our hand to ask questions we show patience and respect.” Classroom contracts must be fair, and for best results, the rewards and consequences must be honored.

I hope that these strategies have helped you begin to formulate an effective behavioral intervention plan in your school. For more related articles, you may also want to read about Classroom Management Strategies that my Students Love and Back-to-School Routines to Start the New School Year. In the next Mondays Made Easy article, I’ll be diving deeper into progressive discipline, mediation, and restorative justice in schools. If you’d like to contribute to the conversation, please be sure to get in touch!